The graphic above is from Matt Blease (@mattblease on Instagram).

The United States is not in a good place. Scratch that – the United States has not been in a good place for a while, but the tears in our nation’s fabric have become glaringly obvious. The murder of George Floyd was the match that ignited a, in the words of renowned Black activist Angela Davis, “global challenge” against the police brutality, racism, and systemic injustice faced by Black Americans to a momentous level. This movement is not new – according to rising senior Laurence Lundy, the Black Lives Matter movement as we know it was founded in the wake of Trayvon Martin’s death in 2012 and “has been a rallying call for Black people and those wronged by the justice system and the systemic ills that plague society today.” Lundy’s nuanced description is notable in that it dismantles a (hopefully diminishing) popular belief that Black Lives Matter focuses on only Black Americans at the expense of other Americans. Rising senior Lexxi Clinton elaborates on this by stating that “the [Black Lives Matter] movement is focused on changing the narrative and systematic oppression and deaths as common or unimportant as they are currently treated.” Rising junior Taylor Johnson emphasizes that the movement is “not something just Black people should be behind, but everyone.”

In turn, this movement has incited a wave of social media activism as users post quotes, petitions, resources, and donation links to support the fight for Black Americans. I have come across these posts in high volumes across my digital landscape – from Instagram to Twitter and even Tinder (Romance & fighting for human rights? Sign me up!). However, there is still a substantial amount of people, including our peers at SMU, who have remained quiet or worse – seemingly unaffected. Even a number of people who were posting profusely a week ago have slowed their support online. Let’s unpack why this lack of vocal support for Black Americans is an issue.

To consume American culture means to consume Black culture. Black Americans have influenced culture and popular trends for years. As Lundy puts it, “Black people are the blueprint.” Through the works of Little Richard, Aretha Franklin, Louis Armstrong, Whitney Houston, and many other Black musicians, Black Americans have not only pioneered, but also heavily influenced a varied swath of musical genres including rock n’ roll, jazz, and pop. Literature by Black authors from Zora Neale Hurston and Langston Hughes to Toni Morrison and Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie has set standards in terms of engaging with difficult themes and speaking frankly about American society while opening doors for other writers of colors. However, there’s no need to look far in the past to see the influence of Black culture on the American mainstream. Music by Black artists has dominated mainstream music in production styles, lyricism, and even releasing styles (see: the cultural shift embodied by Beyoncé’s self-titled album). Black musicians and Black celebrities in general are frequently featured by brands in an attempt to engage with consumers given that Black celebrities are “among the most well-known, influential marketable personalities and trendsetters across the entertainment landscape.” Names like Beyoncé, LeBron James, Oprah Winfrey, and Will Smith bring in star power for brands to match their products with familiar faces. Trends and discussions on social media are driven by Black creators and influencers, including dances to songs like Megan Thee Stallion & Beyoncé’s “Savage”, K Camp’s “Lottery”, and Travis Scott & Young Thug’s “OUT WEST,” memes, and reaction images using stars like Tiffany “New York” Pollard, NeNe Leakes, and Nicki Minaj. Even the language used on social media (yas, slay, lit, boujee, periodt, lowkey, sis – the list goes on) heavily borrows African American Vernacular English (AAVE), particularly using words and phrases popularized by Black women and the Black LGBTQ+ community. Lundy points out that this co-opting is even more frustrating considering that “no credit is given” to Black influencers behind the trends that “they thought up in the first place.” Rising junior Tyne Dickson notes that “most people [seem to] rather enjoy the trend or music without acknowledging the source, and without learning about the source.” Recalling a quote, rising junior Bethany Bass expresses a similar sentiment: “they want our rhythm, but they don’t want our blues.” At the very least, the timeless, significant contributions of Black culture to the mainstream culture that we all actively and inactively partake in makes it imperative for us to advocate for justice when it comes to unfair infractions against Black Americans.

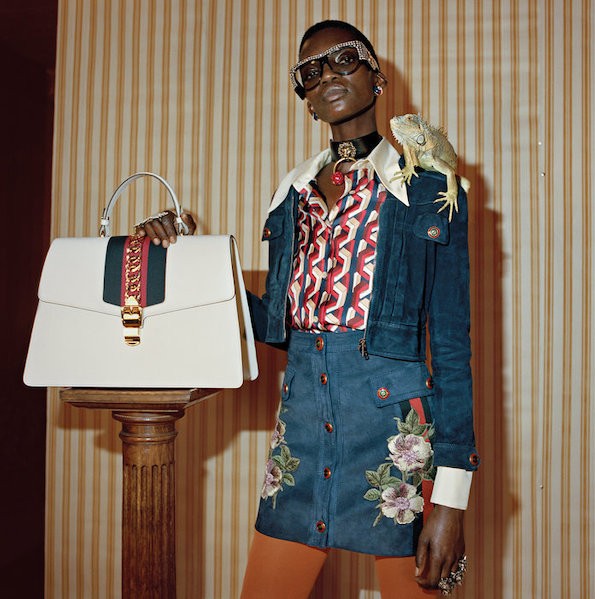

In addition to influencing culture as a whole, Black Americans have left their impact on fashion from the designing end to the business end. In 1970, Jay Jaxon, a Black law-student-turned-fashion-designer, became the first American to lead a French haute couture house when he took the helm of Jean-Louis Scherrer. Virgil Abloh, the founder and CEO of Off-White, is the first Black artistic director of Louis Vuitton’s men’s wear collection (although he has drawn considerable criticism for his half-hearted donation to protestors). Building off the aforementioned star power of Black celebrities, brands have partnered with Black stars, particularly those in music. These partnerships are endless: A$AP Rocky for Dior Homme, Pharrell Williams for Chanel, Saweetie for PrettyLittleThing, Gucci Mane for Gucci, Travis Scott for Helmut Lang, and Nicki Minaj for a slew of brands (Fendi, Roberto Cavalli, Diesel, etc.). Partnerships gave way to popular Black-owned brands including Beyoncé’s IVY PARK, Rihanna’s Fenty, and Kimora Lee Simmon’s Baby Phat. Black Americans’ influence on fashion does not end at big brands and partnerships – many trends have borrowed from Black culture like big hoop earrings while other trends like box braids have been forcibly taken. Much like their influence on greater pop culture, the influential fashion of Black Americans largely goes uncredited. Even on her Instagram feed, rising sophomore and fellow LOOK digital writer Princess Matthew-Mba noticed that she did not see many icons of color, asking herself “How many of the models that I look up to fashion-wise are people of color? Why am I not following [models like] Naomi Campbell?” However, she noticed that she followed stars like Kim Kardashian, who is notorious for appropriating Black fashion. Clinton, who serves as the President of SMU’s Association of Black Students, states that the appropriation and subsequent profits reaped by stars like Kardashian is “another example of how African Americans [are] mistreated in this country.” For Bass, the silence of these appropriating stars is disheartening. “As a Black woman,” she mentions, “I am incredibly upset that people want our culture so bad, but do not want to respect Black bodies.”

The realm of fashion as it stands today would not be the same without the influence and work of Black designers, creators, and stylists. While the current movement on social media is focused on the systemic injustice against Black Americans by law enforcement, it’s important to understand that Black Americans do not solely face injustices in this realm. Black Americans’ unsung impact on fashion emphasizes the need to respect Black Americans in all spaces, including through the Black Lives Matter movement. Fashion by Black Americans, particularly Black women, is frequently disrespected as “ghetto”, “urban”, and “ratchet” before being, as rising junior Abena Marfo puts it, “whitewashed [into] trendy and fashion-forward [ideas]” like “epic” cornrows, “soulful” baby hairs, and durags fit for Givenchy. In describing the appropriation of Black fashion, Johnson, who also serves as Student Senate’s Diversity & Inclusion Chair, remarks that “Black fashion is often called ‘ghetto’ until proven fashionable.”

In addition to stopping cultural appropriation, a much-needed solution in fashion is to include and amplify more Black talent. Dickson suggests that “huge fashion brands can…hire more Black artists, fashion designers, photographers, etc.” Recalling the use of Bantu knots on White models at Marc Jacobs’ Spring/Summer 2015 runway show, Clinton suggests that this hiring is the least that these brands can do for “stealing and disrespecting [Black] culture [while] not even employing Black models.” Even at LOOK, we can bring on more Black writers, stylists, and editors among other talent. Johnson mentions that “one of [her] friends (a Black girl) has applied for [the] SMU LOOK magazine almost three times now, [but] was turned down each time.” Johnson adds that this friend “asked if she could just shadow and [she] was turned down [even though] these same people compliment her on her outfits when she walks into class… that doesn’t make sense.” Supporting the Black Lives Matter movement requires action now to fight against systemic injustices and future action to support equity for Black Americans and their work, whether at SMU or on a broader scale. Emergency support during moments of tragedy is simply not enough.

As a part of the SMU community, it is even more vital for us to support Black Americans and the fight against systemic racism. The Hilltop, teeming with a student population of which 5.2% is Black, takes pride in its location in fresh, business friendly Dallas, where only 17.6% of Black high school students demonstrate college readiness and only 21.37% of Black adults have a bachelor’s degree or higher compared to 67.36% of White high school students and 60.23% of White adults in the same categories. These findings are even more troublesome when considering that Black citizens experience the highest levels of unemployment, child poverty, infant mortality, child food insecurity and faulty internet access among other equity indicators in Dallas. Drawing from her work with Congresswoman Eddie Bernice Johnson, Clinton points out that Black residents of Dallas are also frequently marginalized due to rampant gentrification, “pushing Black families out of their neighborhoods.” Focusing on justice and government issues, Black individuals in Dallas are arrested at the highest rates (82.3 per 1,000 arrests while arrests of White, Hispanic, and Asian individuals are at 30.57, 24.98, and 6.77 out of the same number). Much like the national trend, Dallas’s criminal response system includes a disproportionate number of Black individuals as Black minors have the highest juvenile detentions, Black adults are booked into jails at the highest rates, and Black defendants pay the highest average costs in fines and fees. The clear inequity that exists between White residents and residents of color, particularly Black residents, in Dallas is distorted by the “campus bubble” that Marfo, who serves as the President of SMU’s African Student Association, says “causes a lot of [SMU] students to see nearly everything through rose-tinted glasses” with a perspective “far from reality, especially in Dallas.” While the statistics lead to an acknowledgement of systematic racism in Dallas, Bass, who serves as the Vice Administrative Director of SMU’s Human Rights Council, says that “students need to work to combat racism,” which would require the elimination of our SMU bubble. To pop this bubble, Dickson, who is leading the Black Lives Matter coalition at SMU with her friend, Laura Scott Cary, recommends that the “SMU curriculum…do a better job of discussing and educating these institutional inequities” and that “students…get out a bit more” to see the world beyond the bubble. “Living in a bubble,” Lundy says, “only hurts your ability to reason with and talk to people outside of your particular in-group.” Furthermore, every degree by which inequity grows increases our bubble’s obscurity while allowing harmful stereotypes and societal injustices to fester.

While I highlight Black Americans’ immense influence on culture, trends, and fashion in addition to the systemic inequities marginalizing Dallas’ Black residents to make the case to support Black Americans, it shouldn’t be necessary. “The [Black Lives Matter] movement is more than just a trend,” Marfo says, “it is a pressing human rights issue that has been ignored for far too long and voicing out [against] police brutality is just the tip of the iceberg.” At the root of it, we live in a country that boasts freedom, individuality, and equality, but those tenets have left out the aspirations of Black Americans. The prolonged injustice that exists in our country is enough cause to support Black Americans in the fight against police brutality. This injustice should also fuel us to continue fighting against systemic racism wherever we see it – in law enforcement, education, healthcare, fashion, etc. Acknowledging our convoluted systems is a major aspect of becoming educated about race relations in the United States, which Dickson highlights as a way for people to recognize their privileges. After all, it is the system in place that perpetuates the indoctrination of racism and discrimination in our society with the help of privileged people who align themselves with these abhorrent beliefs.

The question is – how does one go about educating themself on systematic injustice? The right frame of mind matters; Matthew-Mba encourages students to be “willing to have…tough and uncomfortable conversations about race with people”, “to take responsibility if they have ever offended others, and [to] always [speak] up to the injustice… around them.” On campus, both Clinton and Dickson encourage students to attend and support events put on by their Black peers. On a broader level, Johnson suggests that students learn “how to be allies and properly advocate [by raising] funds, awareness, and [educating] their peers that might still be stuck in ignorant ideals.” Marfo emphasizes this last point by stating that “you can’t expect change if you don’t call people out.” According to Bass, this vital change requires the amplification of Black voices both globally and at SMU. Supporting Black voices is one of many key actions that we can take to make sure that “Black Lives don’t stop Mattering [sic] after it stops being popular.”

As you go through this enlightenment of sorts, remember that Black people do not have the sole responsibility to educate you. In fact, Lundy, who serves as the Treasurer of Black Men Emerging at SMU, points out that forcing this responsibility onto Black individuals requires mental fortitude that every Black person may not possess. “Trauma after trauma is inflicted upon us for the color of our skin,” Lundy says. “And the fact that it’s taken so long for people to come to terms with just how sadistic and unconcerned the government is with actually addressing and dealing with the nation’s unhealed wounds is extremely depressing.”

I am not an expert on race issues in America or on the affairs of Black Americans. I am simply a human being concerned for the security of human rights for other human beings. I do not and cannot fully understand the nuances of being Black in America, but I urge other non-Black individuals to learn about these nuances and to fight for justice for all. “Protect EVERY [sic] Black life,” Lundy emphasizes. “If you have room for transphobia, homophobia, misogyny/sexism, ableism, or anything of that affect, you are simply hurting the marginalized sub-groups of an already oppressed minority.” As a gay non-Black person of color, I am continuing to learn about issues that Black Americans face. Doing so helps me understand how I can be a better ally in order to give thanks to groundbreaking Black leaders like Marsha P. Johnson and Andrea Jenkins and to be there for my Black friends by advocating for their livelihood. If the murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Ahmaud Arbery have not spurred you to similarly advocate, then what will it take? The death of another Sandra Bland? Another Tamir Rice? Another Philando Castile? Another Kenneka Jenkins? Another Trayvon Martin?

Our current system is failing Black Americans in ways that are drawing international ire and avoiding the issue will continue to rip up our nation’s fabric. Marfo warns against this continuing deterioration by urging students to “continue advocating and supporting [Black Lives Matter]” even as media attention dies down. The “trendification” of the Black Lives Matter movement on social media and greater media coverage is troublesome as Bass expresses that “it’s scary to think that people only care about Black issues when they can get 1,000+ likes on a black tile and deleted later because it messes with their aesthetic.” It’s up to us to be committed to education and justice so that we can weave the forgotten pieces into this fabric and make it represent every shade and every background of American society. “There is a shift happening in American society and politics,” Dickson notes. “The readers of this very [publication] and myself hold the power to change this world for the better.”

To get involved, start by consulting this non-exhaustive list. Donations, participation, and support are vital. Posting a tastefully designed Desmond Tutu quote on your Instagram story will not cut it for long.

Dallas Resource Guide compiled by Jess Pires-Jancose

Actions for Solidarity: #BlackTransLivesMatter

Boss Women Media’s Black-Owned Businesses Directory

CR Fashion Book’s “BLACK FEMALE WRITERS WHO CHANGED FEMINIST THEORY”

The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness by Michelle Alexander

Are Prisons Obsolete? by Angela Davis

How to be An Anti-Racist by Ibram Kendi

How to Be an Ally as a College Student by @homefromcollege on Instagram

DONATE TO:

National Black Justice Coalition

DFW Student Coalition for Justice